The Brothers on the Central Monaro Plains (Photo by Dr. Dennis Williamson © 2024)

BY DR. DENNIS WILLIAMSON

Copyright © 2025 by Dennis N. Williamson and Geoscene International (a division of Scenic Spectrums Pty Ltd). All rights reserved.

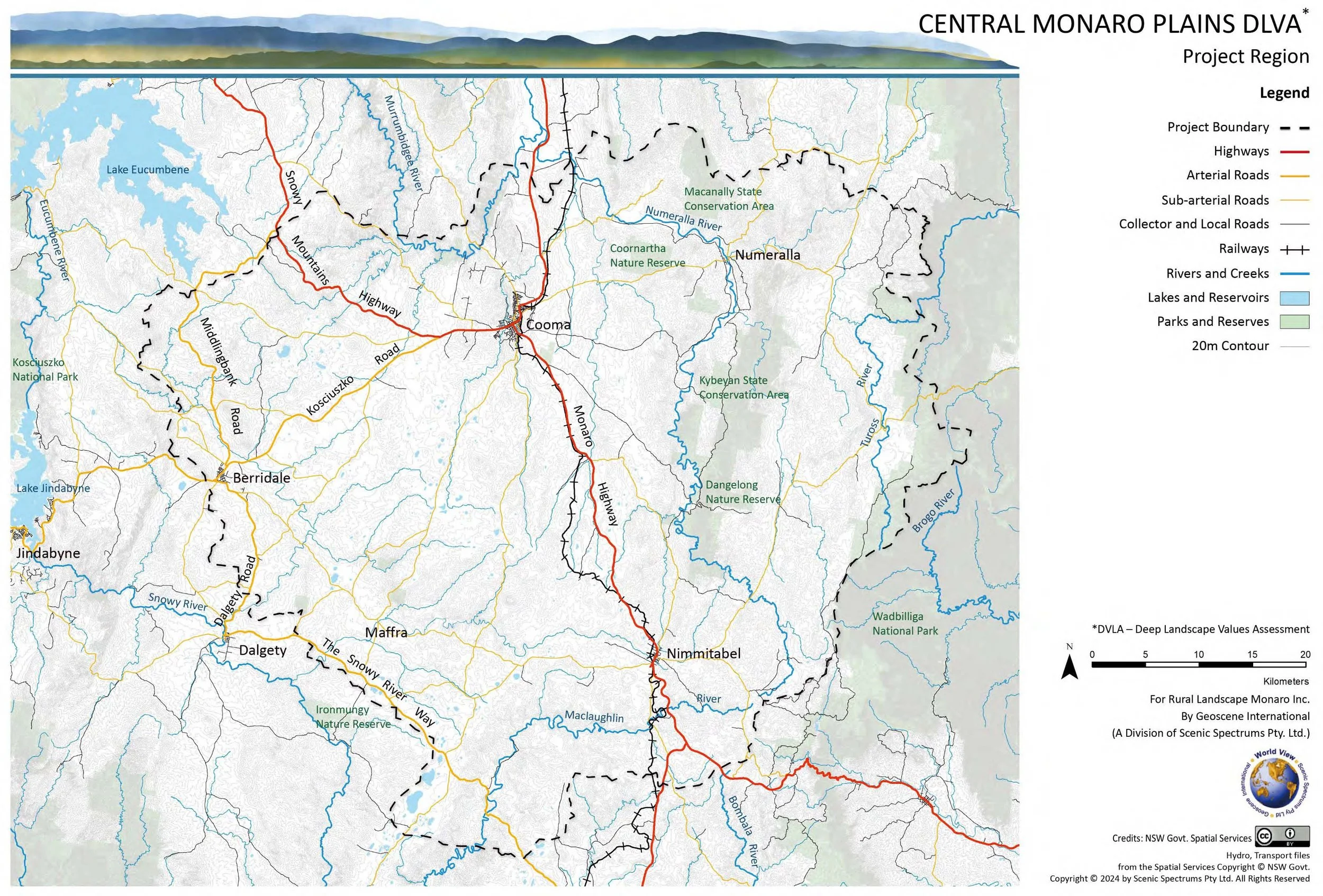

During 2024-25, the Central Monaro Plains Deep Landscape Values Assessment was prepared by Geoscene International on behalf of a Cooma, New South Wales region community group - Rural Landscape Monaro Inc.

This research study of the Central Monaro Plains (CMP) has created quite a journey, not measured simply in kilometers or hectares, but also in people met or read about and in the great knowledge gained regarding the landscape values of this South East New South Wales region. It is for good reason that this project is called the Central Monaro Plains Deep Landscape Values Assessment.

The Central Monaro Plains (CMP) region covers over 336,000 ha of land located about 90 km South of the Australian capital city of Canberra, ACT). It stretches 75 km or so east to west from the Great Escarpment across the Kybeyan Range and the Great Divide (Monaro Range) to near Varney’s Range just west of Berridale. It extends and nearly 70 km from the Chakola vicinity north of Cooma southward over the Great Divide before reaching the Maclaughlin River and the Snowy River Way.

This project is what we call a ‘deep landscape values assessment’ (DLVA). The primary focus is the rural and natural landscapes of the central Monaro region. The landscape values of the regional townships and urban areas of Cooma, Berridale, Numeralla, and Nimmitabel are not addressed. An extensive amount of information has been documented, identifying multiple environmental, ecological, tourism, scenic, and cultural heritage (Aboriginal and Non-Aboriginal) attributes of varying landscape value. Some of the highlights of these findings and mapped information are provided in the Vol. 1 Summation section of the report.

The CMP project does not address the commercial or economic values of mineral, forest or agricultural resources, etc. Those types of land uses and values are already considered by the NSW statutory and strategic land planning system through various regional strategies, Local Environment Plans (LEPs) and various government and Independent Planning Commission reviews of major project proposals. Specific proposed land developments are not addressed in this report. Existing landscape alterations are assessed generally in terms of their positive or negative effects on existing scenic quality. Broad biodiversity and landscape management recommendations that mention selected types of land use or landscape alterations are also provided.

What has been learned about this region now fills six volumes of the entire report. Each volume is a stand-alone document but is interdependent on the other volumes. Volume 1: Summation presents a brief overview and highlights of our learnings. Some of the key things we have rediscovered include:

1. The Monaro Volcanic Province (MVP) is a 4,200 km2 area of regional to international significance which also provides a useful analogue region for research of Mars. Combined with granitic plutons and outcrops, the geology, along with soils, create the backbone of landscape values for the CMP region. Over 200 natural maar lakes are associated with the MVP region.

Volcanic Maar Lakes and Naturally Treeless Plains near Hazeldean Homestead (Photo by Nick Fisher, undated - Panoramio - CC)

2. The Monaro hosts the most extensive area of remnant Temperate Montane Grasslands in Australia. These coincide with naturally treeless nature of areas on red-chocolate basalt soils to make the elevated plains landscape of the Monaro highly significant in the Australian context.

3. The Central Monaro Plains is of national and state significance due to its combination of potentially six Threatened Ecological Communities (TECs) listed as Critically Endangered or Endangered under the Commonwealth EPBC Act 1999 and/or the NSW Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016. There are 24 native plant species and 27 native animal species that are listed as Critically Endangered or Endangered. There are 16 native plant species and 54 native animal species that are listed as Vulnerable.

Critically Endangered Button Wrinklewort (Rutidosis leptorhynchoides - Photo by Harry Rose © 2014. In Flickr, Creative Commons 2.0. )

Endangered Monaro Grassland Earless Dragon (Tympanocryptis osbornei - Photo by Tim McGrath © 2015 - with permission)

4. High Overall Environmental and Biodiversity Conservation (EBC) Landscape Values exist in over 60% of the CMP region and very little of the region is of low value in this regard.

5. Tourism is the most important economic sector of the broader Snowy Monaro Region, with over one million annual visitors generating $738 million in direct expenditures and an additional $354 million in gross value-added expenditure while creating over 5,000 jobs. The CMP region offers a variety of key landscape features, activities, events, and services that attract and provide for visitors. This creates a significant asset for the regional community and the State of NSW.

The key landscape features contribute to the Scenic Landscape Value of the CMP region. The region is described as having two Landscape Character Types (LCTs) with 13 Landscape Setting Units (LSUs). Our assessment of the region’s scenic quality, viewpoint sensitivity levels, and visibility distance zones has resulted in the mapping of High, Moderate, and Low Overall Tourism and Scenic Landscape Values, of which almost of half of the region is assessed as high value.

6. The Indigenous people of the Monaro have existed on the Monaro for an estimated 10,000 to 25,000 years - long before European colonisation. Their story and key cultural heritage values are summarised in Volume 5 of this report. The Monero or Ngarigo language group occupied most of the CMP region, while the Yuin language group extended from the South Coast up to the top of the Great Coastal Escarpment and onto the eastern and southeastern areas of the CMP region.

Although assessment of the relative value of such cultural heritage is complex, with the generous assistance of some of the Indigenous descendants of the Monaro, we have been able to provide a rudimentary picture of how their rich cultural and spiritual connection with Monaro Country is related to the landscape geographically. We have found that High Overall Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Values are associated with nearly 75% of the region.

Here we fully acknowledge that the Indigenous People of the Monaro do not traditionally categorise the value of their Country in terms of high, moderate, or low. They see their Country holistically and spiritually as being of immeasurable value in its entirety. However, to place this value in the context of present-day Non-Aboriginal thinking for land management purposes, we have categorised those values in relative values. However, we use the term ‘Unknown Values’ instead of low values due to our lack of complete knowledge.

7. Our assessment of Non-Indigenous Cultural Heritage covers the colonisation of the Monaro by European and other Non-Aboriginal people since 1823. The historical and cultural significance of sheep and cattle grazing to the regional and national legacy has been described. The historic travelways, many of which followed traditional Aboriginal travelways, have been mapped as accurately as possible. Fifty-eight rural pastoral heritage sites are listed under the NSW State Heritage Register or in the Heritage SEPP schedules of the Local Environment Plans within the CMP region. Another 33 listed heritage sites include pastoral residences, public buildings, hotels and inns, cemeteries and grave sites, churches, railways and railway bridges, industrial and mining sites. Our assessment associated nearly 70% of the region with High Overall Non-Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Landscape Value.

8. The influence of the Monaro landscape on cultural heritage is strongly reflected in literature and the arts. This is repeatedly demonstrated through books, poetry, and songs about the region, its sweeping grasslands, its woodlands and forests, streams and lakes, plants, animals and birds. The Aboriginal cultural heritage connectivity to Monaro Country is beginning to re-emerge in a public manner through the paintings of Indigenous and the sharing of Dreaming Stories by the Monaro’s Indigenous knowledge keepers. The literature and arts clearly demonstrate how the Monaro’s landscape setting has shaped the Monaro community and influenced the lives of the people. Such aspects are sometimes difficult to pin down geographically in a specific way. However, ‘Areas of Attraction for Film/Art Settings’, which focus on the plains landscapes west of the Kybeyan Range of the Kybeyan State and Dangelong Nature Reserves, have been mapped and assessed as an area of High Overall Non-Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Landscape Value.

9. Volume 6 of this report provides an evaluation of the Overall Landscape Significance of the CMP region. Through the composite mapping and quantitative weighting of the diverse range of environmental, biodiversity, tourism, scenic, and cultural heritage factors and values assessed in Volumes 2, 3, 4, and 5, the percentage of high, moderate, or low/unknown significance for four value themes are as follows:

Environmental and Biodiversity Conservation Landscape Values (EBC)

Tourism and Scenic Landscape Values (TS)

Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Landscape Values (ABH)

Non-Aboriginal Cultural Heritage Landscape Values (NBH).

High overall landscape significance has been assessed over 49% to 74% of the CMP region for these four value themes.

10. The Overall Landscape Significance resulting from the spatial combination of the above twelve different landscape value categories yields a complex mosaic of values across the Central Monaro Plains region. To assist in making this complex mosaic of values clearer and easier to understand, two alternative methods for categorising them into Very High, High, Moderate, and Low Landscape Significance have been applied:

the Weighted Numeric Values method; and

the Weighted Value Standard Deviations method.

The relative Overall Landscape Significance ratings based on The Weighted Numeric Values method for the CMP region are as follows:

Very High Overall Landscape Significance ~43%

High Overall Landscape Significance ~45%

Moderate Overall Landscape Significance ~12%

Low Overall Landscape Significance 0.10%

The relative Overall Landscape Significance Based on the Weighted Value Standard Deviations method is as follows:

Very High Overall Landscape Significance ~53%

High Overall Landscape Significance ~35%

Moderate Overall Landscape Significance ~11%

Low Overall Landscape Significance ~0.52%

When we immerse ourselves in the entire spectrum of the cultural heritage values of the Monaro, Aboriginal and Non-Aboriginal, we can more fully appreciate the region’s extensive significance and value. This is a landscape that has worked its way into the pulse and bloodstream of every type of person who has ever lived on the Monaro, as well as visitors who only travel through. Even people who have never travelled to the Monaro may be dramatically affected by it through books, poetry, music, or the film arts.

This is a landscape that is not only important to those who live there, but to thousands of others who have been vicariously affected by it. This is not just a local or district landscape of passing note, but a landscape of regional and national significance and value to NSW and to Australia. Commenting on the importance of the Monaro to Australia’s film industry, film location specialist Chris Reynolds (2023) has remarked that, “The unique treeless landscape of the Monaro Plains has for decades drawn film makers to the region, as there is no other region in the country that offers the scale and topography of the sweeping vistas on offer.”

The heritage attributes and values may not be fully visible or known, but our knowledge of them helps us to better understand the backstory of our cultures and the landscape to which we have connection – who we are, where we came from, what happened where and when to influence and shape what exists today. Cultural attributes and values give meaning to the landscapes we live in or visit – making landscapes not simply another place in space, but also in time and in the lives of past and present people. As such, the Monaro landscapes reflect more than just the landforms, vegetation and waterforms that we can see with our eyes but also places and settings of history and culture that we can understand and appreciate with our mind’s eye.

For the reasons outlined here and documented in detail throughout this report, the landscape values of the Central Monaro Plains should be treated with the highest regard by the community and by the government agencies who represent the community. This is indeed a very special region of Australia that deserves our utmost understanding, respect, and care.

If you would like to read the full Summation in Vol. 1 of the Central Monaro Plains Deep Landscape Values Assessment, please go to our OneDrive at this weblink:

1 CMP DLVA Vol1 Summation Gesoscene 280225cs.pdf

Further blogs summarising further volumes of this report will be posted in future.

Poa Tussock Grasslands on the Monaro at One Tree Hill (Photo Dr. Dennis Williamson © 2024)